query-json: jq written in Reason

query-json is a faster and simpler re-implementation of jq's language in Reason, compiled to a native binary and to a JavaScript library.

It's a CLI to run small programs against JSON files, the same idea as sed for text. As a web engineer, it's an essential tool while debugging HTTP APIs or exploring big JSON files (like those from AWS Config).

I started the project with the goal to create something useful and learn during the process. I was very interested in learning how to write a parser and a compiler using the OCaml stack: menhir and sedlex, and finally try to compile it to JavaScript.

This post explains the project, how it was made, the decisions I followed, and some reflections.

#Why I wanted to learn parsers/compilers

I had a vague idea about the theory, but nothing practical. It was the right time since I had made styled-ppx, a ppx (PreProcessor Extension) that allows CSS-in-Reason/OCaml. It needs to parse CSS and do some code generation for bs-emotion.

I asked @EduardoRFS for help writing a CSS Parser that supports the entire CSS3 specification and he came up with something. That "something" is a project I want to understand, improve, and maintain over time.

#How query-json works

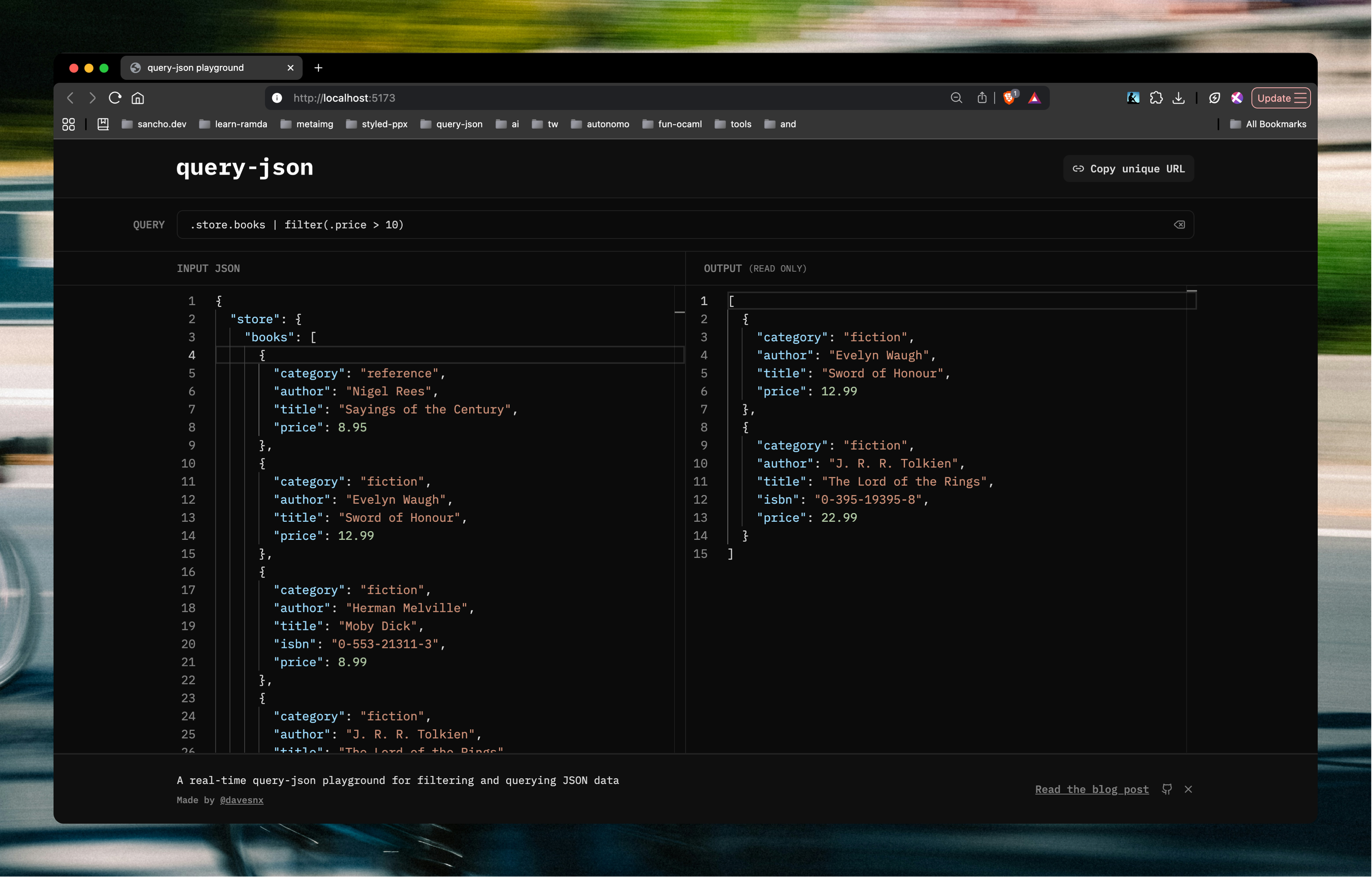

query-json ".store.books | filter(.price > 10)" stores.jsonThis reads stores.json and runs the query ".store.books | filter(.price > 10)" against it.

The query describes a jq program. By running it, it accesses the "store" field, then the "books" field (since it's an array), runs a filter on each item by its "price" (larger than 10), and finally prints the resulting list.

[

{

"title": "War and Peace",

"author": "Leo Tolstoy",

"price": 12.0

},

{

"title": "Lolita",

"author": "Vladimir Nabokov",

"price": 13.0

}

]The semantics of jq consist of a set of piped operations, where each output is connected to an input where the first input is the JSON itself. Some pseudo-code to illustrate:

{ /* json */ } | filter | transform | count | .field

In order to transform the query to a set of operations that run against a JSON, we will divide the problem into 3 steps: parse, compile and run.

#Parsing

Parsing is responsible for transforming a string into an AST (Abstract Syntax Tree), a data structure that contains the same information as the input, but in an easier shape to work with. In case the input is malformed (not following the rules), the parser can also return errors.

One of the beauties of jq is that all the expressions are piped by default, so .store | .books is equivalent to .store.books. I designed the AST to represent the pipe structure in its nature. If you want to know more about jq's language, check their wiki.

Let's see an example. When the parser receives .store.books it will return:

Pipe(Key("store"), Key("books"));All the operations are transformed into these constructors from above (Pipe, Key, etc.). Those constructors are called Variants.

Variants model values that may assume one of many known variations. This feature is similar to enums in other languages, but each variant may optionally contain data that is carried inside. Variants belong to a large group of types called ADTs.

The entire query-json AST is one big recursive variant.

Following with a more complex example, let's parse .store.books | filter(.price > 10):

Pipe(

Pipe(Key("store"), Key("books")),

Filter(Pipe(Key("price"), Literal(Number(10))))

);Here you can see how Pipe is used both as the pipe | and as .store.books. You can see more examples in the parsing tests.

#Compiling

The compilation step receives the AST expression and transforms it to code. The compiler is a big recursive pattern match, which is another great feature of Reason/OCaml and looks something like this:

let rec compile = (expression, json) => {

switch (expression) {

| Empty => empty

| Keys => keys(json)

| Key(key, opt) => member(key, opt, json)

| Index(idx) => index(idx, json)

| Head => head(json)

| Tail => tail(json)

| Length => length(json)

/* [...] */

}On the left side are defined all the possible Variants and on the right side each operation. Those operations transform the JSON. Here is where map, filter, reduce, index, etc. are implemented. In the real implementation, many branches call compile recursively.

#Running

The easier part: the compile step gives us back a curried function that expects a json as the only argument. We just apply the function to this JSON and print the result.

This example only describes the happy path. In reality, the parsing and compilation steps return a result type which allows handling errors.

let compile: Ast.expression -> Json.t -> (Json.t list, string) result#Distribution

Now we've covered how it works internally and a brief overview of the architecture. Let's dive into how developers can use it on their machines.

#How to compile it

query-json is built with dune, which supports ReasonML out of the box. dune (by default) can run the OCaml compiler with different backends. It can compile to bytecode (and run with the bytecode interpreter) or it can compile to binary to make a native executable.

All of the build process and tests run on our CI in GitHub Actions: running Mac, Windows, and Linux images. I distribute the pre-built binaries for all architectures in the GitHub Releases and the npm registry.

This allows users to download it directly via npm, or from the GitHub release page.

#How to compile to the web

Apart from compiling to the executable, query-json is compiled to JavaScript as well.

Compilation to JavaScript is the sweet section of this blog post and the part I'm most proud of. It wasn't a big effort, since the tools I used are already mature, but being capable of releasing 2 distributables from a single codebase feels like magic, considering all query-json's dependencies (menhir, sedlex, and yojson).

To accomplish this, I used js_of_ocaml (jsoo for short). jsoo is a compiler that uses an intermediate representation of the OCaml compiler (the bytecode I mentioned before) and transforms it to JavaScript.

Since dune supports jsoo out of the box, I just needed to modify its stanza by adding (modes js):

(executable

(name Js)

(modes js)

(libraries console.lib source yojson js_of_ocaml))After running dune build, I had a big file Js.bc.js with all the code bundled. Kind of amazing, tbh.

#Building query-json's playground

After compiling to JavaScript, I built a web playground where people could try query-json without installing anything. This made the tool immediately accessible—no downloads, no setup, just open a browser and start typing.

Beyond user accessibility, the playground brought some nice benefits: I could deploy preview versions on every pull request, users could share bug reports via a single URL, and everything ran faster since it executed locally in the browser.

The playground is built with jsoo and a few cool dependencies: jsoo-react and jsoo-css. You can try it yourself here:

https://query-json.netlify.app

The query-json execution runs on each keystroke, which means the playground runs offline. Comparing this with the official jq playground, which needs to communicate with a backend, run jq there, and return the response, it's night and day.

Having a playground as a serverless frontend app is a massive improvement over a backend-dependent one. Faster, safer, more scalable and accessible to everybody.

#Benefits

Using jsoo seems a powerful way to run your OCaml code in a browser without much hassle. This was a key takeaway for me while making this project possible. But distribution isn't the only benefit—here's a list of other upsides in my opinion:

- Portability: moving code from server to client or vice versa, sharing marshal/unmarshal code, easier contract testing.

- Familiarity: writing the same patterns benefits newcomers who need to learn fewer platform-specific rules.

- Usage of OCaml's ecosystem: access to many libraries and ppxs and latest OCaml features.

- New possibilities: some apps might benefit from server-side rendering, others from moving functionality offline, and many app-specific designs that are unblocked by this.

Most of the REPLs from Reason, OCaml, Flow, and ReScript (all written in OCaml) use js_of_ocaml for their playgrounds.

#Future

query-json is still young. It supports most of jq's core features, but there's room to grow—and maybe diverge.

The future of query-json is to support more constructors from the jq language and provide a better experience for running operations on JSON by having better error messages and better performance.

For me, jq is like a double-edged sword—very powerful but a bit confusing. The number of questions on StackOverflow.com proves that there are many problems without a solution in the language. If query-json gets a lot of traction, I would diverge from the jq syntax and try to solve those confusing parts.

The other mission of query-json is to push performance forward. Now we are implementing most of the missing functionality, and next is to explore performance optimizations, such as:

- Improving the JSON parsing, such as JSON streaming, or even better, only parsing the parts that the query needs

- Refactor it using OCaml multicore (once it's published!)

- Replacing menhir with a hand-written parser

#Final

I hope you liked the project and the story. Let me know if you're interested in these topics. I'm always happy to chat.

Thanks to everyone who reviewed this blog post: Javi, Enric, and Gerard.

Thanks for reading! If something's unclear or you think I'm wrong, tell me. Feedback is appreciated.

@davesnx